Once, there were unicorns.

Long ago, when we were desert wanderers, G-d/dess instructed us to make a portable sanctuary, so that S/he could dwell amongst us:

וְעָ֥שׂוּ לִ֖י מִקְדָּ֑שׁ וְשָׁכַנְתִּ֖י בְּתוֹכָֽם׃

And let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them. – Exodus 25:8

The instructions S/he gave were detailed – an ark of acacia wood overlaid with pure gold and cherubim fashioned on top; a menorah with cups shaped like almond blossoms; cloths of blue, purple and crimson yarns; a tent covering of ram skins, and more.

One of the instructions asks for the skin of a particular animal – the tachash (תחש) – to be part of the tent covering:

וְעָשִׂ֤יתָ מִכְסֶה֙ לָאֹ֔הֶל עֹרֹ֥ת אֵילִ֖ם מְאָדָּמִ֑ים וּמִכְסֵ֛ה עֹרֹ֥ת תְּחָשִׁ֖ים מִלְמָֽעְלָה׃

And make for the tent a covering of tanned ram skins, and a covering of tachash skins above. – Exodus 26:14

The tachash skins aren’t the only animal products called for in the creation of the mishkan, the desert sanctuary where our ancestors worshipped. However, there’s something unique about them – there’s some disagreement about what they were. The JPS translation says they were “dolphins,” with a sheepish asterisk that says “or dugong; meaning of Hebrew tachash uncertain” (JPS on Exodus 25:4). However, when the ancient rabbis discussed the tachashim, their descriptions don’t correspond to any animals we’d recognise in the natural world today.

In Shabbat 28a, Rav Yosef says, “we translate the word תחש (tachash) as sasgona, which means that it rejoices [sas] in many colours [gevanim]” (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 28a). This translation originally appears in the Targum Onkelos, the earliest Aramaic translation of the Torah. So, from this we learn that the tachashim were joyful creatures of many colours. Furthermore, according to Rabbi Meir, “The תחש (tachash) of Moses’s day was a separate species, and the Sages could not decide whether it belonged to the genus of wild beasts or to the genus of domestic animals; and it had one horn on its forehead…since he says that it had one horn in its forehead, it follows that it was clean” (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 28a). This means that while difficult to categorise, the tachashim were kosher animals with one horn on their foreheads. Sounds like a unicorn to me! (And to my dear teacher, Rav Kohenet Rabbi Jill Hammer, who first taught me about these creatures.)

In this same text, Rabbi Meir says that the tachash, the unicorn, “came to Moses’s hand just for the occasion and he made the [covering of] of the tabernacle, and then it was hidden (נגנז – nignaz).” I shared this text with my friend, Yael Roberts, who is an amazing Jewish educator and artist – and she had a reading of this that broke my heart. You realise that means they went extinct, she said. From us using them. We killed the tachashim to make the mishkan and then there weren’t any left.

Viewed this way, the tale of the tachashim – the unicorns – is tragic. Once, there might have been magical creatures that roamed the earth, but then we killed them all in the name of creating sacred space.

The word translated above as “was hidden” is “נגנז – nignaz,” which is the passive version of a fascinating root in Hebrew (גנז – gimmel.nun.zayin), which has many different meanings. According to the Jastrow (a dictionary used to navigate early Rabbinic texts), it can mean “to disappear,” “to remove from sight,” or “to be suppressed,” which supports the reading that the tachashim went extinct because of human usage. However, it can also mean “to cut off,” “to set aside,” “to save,” or my personal favourite, “to hide (in order to prevent desecration).” This is also the same root as the word “גניזה – geniza,” the name given to places where Jewish sacred texts are stored once they are no longer in use. In Jewish tradition, Hebrew texts that contain Divine names are considered too holy to just throw out or recycle after we’re finished with them, so we bury them, with the same tenderness with which we’d bury living things. The texts remain in a geniza for safekeeping until they can be buried (and sometimes over the long-term). In some instances, a geniza can mean a treasury (Pesachim 118b), which is unsurprising, given how much we as a people treasure our words.

So, it’s possible that Rabbi Meir’s suggestion means that human behaviour caused the extinction of the tachashim, but it’s also possible that the building of the Tabernacle, which caused a threat to the tachash population, precipitated a need to protect them. Was the result of tachash overuse the creation of a “geniza” for them, a space to hide them in order to prevent their desecration? I’m imagining the ancient version of an animal sanctuary, meant to save our endangered unicorn friends.

Our tradition offers a dynamic tension: on the one hand, we have the concept of tsaar ba’alei chayim, the injunction to minimise animal suffering, and on the other hand, we do have a very clear tradition of animal products being used for ritual purposes. The tachashim are only one example; those reading this article probably picked up that there were ram skins used for the mishkan, as well, and that’s before facing the truth that the mishkan was used as a place of animal sacrifice, as was the Temple in Jerusalem after that. Before the destruction of the Temple necessitated the innovation of the use of words for prayer, sacrifices, including the sacrifice of animals, were how our ancestors prayed. We don’t make animal sacrifices any more for the most part (though the tradition of kaparot remains in some communities), but we do use ritual objects that traditionally are made from animal products – Torah scrolls, tefillin, mezuzot, tzitzit, shofars and more. It can be a difficult decision for the Jewish vegan to reconcile their beliefs about protecting animals with the ritual practices of their people. I believe that the way forward is a creative approach – a dance that honours our tradition, as well as our desire to create a “geniza”, a protective space, for the tachashim of today.

In this article, I explored with Soferet Avielah Barclay how one might go about creating vegan tefillin. It’s worth noting that the regulations about materials for scribing tefillin also apply to mezuzot and Torah scrolls, so it’s not beyond imagining that one could find or create these objects in a way that would satisfy a Jewish vegan. Avielah’s approach was to explore our ancestors’ original intentions around the choices they made regarding the production of tefillin, in order to guide our decisions as contemporary Jews. When our ancestors used animal products for the mishkan, they were trying to make the most beautiful sacred space they could imagine, so that they could feel the presence of the Divine with them on their journey. When they offered up animals, they were trying to cultivate a relationship with G-d/dess. When they wrote down the words of the Divine, they wanted to preserve them in the best possible way, because those words were so important to them. When they made tefillin, mezuzot and tzitzit, they wanted constant reminders of G-d/dess’s teachings. When they blew the shofar, they wanted to hear its heartbreaking cry, to hear a call to wake up. I believe that in remembering, or imagining, what it was that our ancestors wanted in the first instance, we can make creative choices and find a way forward for ourselves as those stepping into the world as both Jews and vegans. And perhaps, by doing so, we are living out Rabbi Meir’s statement that the tachash “nignaz” – was hidden away in order that it be protected, just as we must protect all living creatures.

*

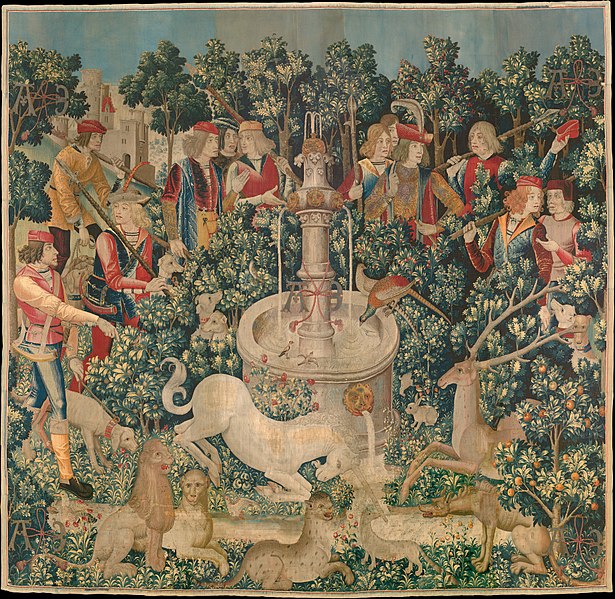

Photo Credit: “The Unicorn is Found” by Unknown Artist, photo from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Kohenet Yael Tischler is a ritual-weaver, Jewish educator and song leader. She is the co-founder of Yelala, a constellation of work that celebrates Earth-centred, feminist Jewish spirituality and reclaims the practices of our women/femme and folk ancestors. She holds an MA in Writing for Young People from Bath Spa University, a BA in English Literature from Columbia University and a BA in Tanakh (Bible) from the Jewish Theological Seminary.

Kohenet Yael Tischler is a ritual-weaver, Jewish educator and song leader. She is the co-founder of Yelala, a constellation of work that celebrates Earth-centred, feminist Jewish spirituality and reclaims the practices of our women/femme and folk ancestors. She holds an MA in Writing for Young People from Bath Spa University, a BA in English Literature from Columbia University and a BA in Tanakh (Bible) from the Jewish Theological Seminary.