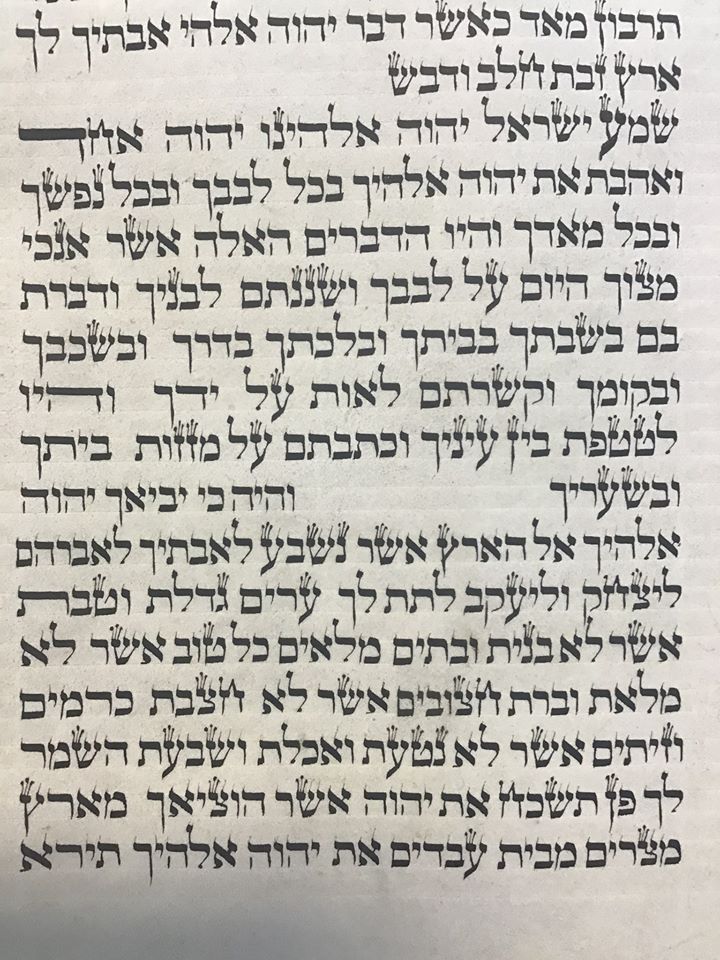

Photo: Shema in the Blue Sefer Torah (written by a Sefardi aider in an Ashkenazi style); credit: Soferet Avielah Barclay

*

וְהָי֞וּ הַדְּבָרִ֣ים הָאֵ֗לֶּה אֲשֶׁ֨ר אָנֹכִ֧י מְצַוְּךָ֛ הַיּ֖וֹם עַל־לְבָבֶֽךָ׃

וְשִׁנַּנְתָּ֣ם לְבָנֶ֔יךָ וְדִבַּרְתָּ֖ בָּ֑ם בְּשִׁבְתְּךָ֤ בְּבֵיתֶ֙ךָ֙ וּבְלֶכְתְּךָ֣ בַדֶּ֔רֶךְ וּֽבְשָׁכְבְּךָ֖ וּבְקוּמֶֽךָ׃

וּקְשַׁרְתָּ֥ם לְא֖וֹת עַל־יָדֶ֑ךָ וְהָי֥וּ לְטֹטָפֹ֖ת בֵּ֥ין עֵינֶֽיךָ׃

וּכְתַבְתָּ֛ם עַל־מְזוּזֹ֥ת בֵּיתֶ֖ךָ וּבִשְׁעָרֶֽיךָ׃

Take to heart these instructions with which I charge you this day.

Impress them upon your children. Recite them when you stay at home and when you are away, when you lie down and when you get up.

Bind them as a sign on your hand and let them serve as a symbol on your forehead;

inscribe them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates.

-Deuteronomy 6:6-9

*

We recite these words every single time we say the Shema, the central prayer of the Jewish people. The prayer is a declaration of the unity of G-d/dess and the Jewish people’s devotion to the One. Every time these words roll off my lips, I feel connected to my ancestors of long ago, to the way that each generation has taught the next the ways of our people. The Biblical verses which make up the Shema are the source texts for the practice of laying tefillin (as well as mezuzot).

For those of you encountering tefillin for the first time, they are small black boxes attached to leather straps. Inside the boxes are the words of the Shema. Jews who take on the mitzvah (commandment) of tefillin bind these boxes to the head and the left arm (or according to some authorities, the non-dominant arm) during weekday morning prayer services. The traditional reason is that they are daily reminders of G-d/dess’s commandments, a physical manifestation of our devotion to G-d/dess, literally binding words of G-d/dess’s teaching to our bodies. Tefillin also have magical resonances (something that I was extraordinarily excited to learn, given that I am still waiting for my Hogwarts letter). According to the academic Joshua Trachtenberg, “The phylacteries (tefillin) undoubtedly developed from some form of amulet or charm, and while their religious nature was already firmly impressed upon them, the Talmud still retained reminiscences of their magical utility in several statements that indicate that they were popularly believed to drive off demons” (Joshua Trachtenberg, Jewish Magic & Superstition, p. 145).

Whatever one’s reasons for wanting to take on the practice of tefillin, they do pose a challenge for the vegan practitioner. Firstly, the prayer scrolls themselves are written on animal skin. If you’re Ashkenazi, they are written on q’laf (animal parchment or vellum), and if you are Sephardi or Mizrachi, they are written on g’vil (tanned or sueded animal skin). Secondly, the straps are made from leather. None of these are kosher for vegans! As an observant Jew who feels very attached to the traditions of my people, as well as a strict vegan, I’ve felt myself in a bind about tefillin (see what I did there). I can’t imagine I’m the only one. I sat down with Soferet (Hebrew scribe) Avielah Barclay to see what advice she had for Jewish vegans hoping to find tefillin that would align with their values.

Avielah’s advice was this: firstly, to understand that the way tefillin look today isn’t the only way that they have ever looked. The Rabbis of the Talmud standardised the acceptable way to make tefillin, but before that time, and even afterwards, people made tefillin loads of different ways. Our ancestors encased the prayer scrolls in pretty much anything – including these pockets found at Qumran (the Dead Sea Scrolls). Furthermore, the leather straps aren’t strictly a halakhic requirement. People used to attach tefillin with ribbons, strings, or other materials – there’s nothing legal to stop contemporary vegans from doing something similar. If you are keen to conserve the leather-y look, I had a separate conversation with Student Rabbi Anna Posner where she mentioned, “Ages ago… I saw a video… that showed people making leather out of pineapple skins…. I concluded from that that please G-d one day we’d have pineapple skin tefillin.” Potentially, pineapple skin tefillin is the way of the future. In the meantime, any material that is strong enough and meaningful to the wearer will do the trick. There’s the recent precedent of these “women’s” tefillin, which use ribbons. While I feel uncomfortable with the idea of branding a particular type of ritual garb as being “for girls,” this at least shows that there are already people using other materials for tefillin straps.

Avielah also shared with me that the traditional ink used by Sofrim/Sofrot (Hebrew scribes) can pose an ethical

question for vegans. The most commonly used ink is made with the tannic acid extracted from gall nuts. A tree produces a gall nut when a wasp flies inside of it and lays her eggs. This causes the tree to have an allergic reaction, which produces the tannic acid. In most cases, the wasps make it out of the gall nuts before they are harvested, flying away to freedom. However, a strict vegan might not feel comfortable with using a product (even though it is technically the by-product of the tree) that an animal had a hand in creating and/or if there is a chance that an animal might have been harmed, however small. For me, this feels like a similar issue to honey, which some vegans feel is okay, but some don’t. Avielah shares that she has successfully made vegan gall ink, by checking to make sure that the gall nuts have holes in them, which means that the wasp has escaped and has not been harmed. Another option, if you don’t want to use gall ink, is that the only universally agreed requirement for scribal ink is that it is black when it’s wet and black when it’s dry, so it’s possible to use certain synthetic alternatives.

Another thing to think about is the writing implement used by the scribe. In Ashkenazi tradition, this is usually a feather from a kosher animal, such as a goose or turkey. However, in Sephardi tradition, it is typical to use reed or bamboo. So, a vegan hoping to avoid animal products all together could decide to follow the Sephardi tradition.

The biggest issue is actually the animal skin itself. Halakhically (according to Jewish law), tefillin does need to be written on skin from a kosher animal. In Keset HaSofer, a compendium of the laws of scribal writing from the 19th century, it states, “It is written ‘therefore let the Torah of God be in your mouth’ (Exodus 13:9) and it is explained from this that we do not write Sefer Torah, tefillin and mezuzot (on anything) except skins from domestic animals (cattle), non-domestic animals and birds that are clean” (Keset HaSofer 2:1). Basically, this means that because Exodus 13:19 says the “let the Torah of God be in your mouth,” it can only be written on animals that can go in our mouths, that is, kosher animals.

Given the Halakhah (Jewish law), there are a few ways that a vegan could approach this. If following the letter of Jewish law is important to you, Sofer (Hebrew scribe) Marc Michaels reminds us that, “animals have never died specifically just to make a Torah (or other sacred objects, such as the scrolls for tefillin). They were slaughtered for food and the skin is a by-product” (Marc Michaels. “Permitted in Your Mouth.” Adventures in Practical Halachah no. 5, p. 2.). For some vegetarians and vegans, it might be sufficient to know that no animals died specifically for their tefillin, and the fact that the skin is being used to make sacred objects effectively means that no part of the animal is wasted. Additionally, Avielah reminds us that tefillin (as well as mezuzot and Torah scrolls), can be written on kosher nevelah animals, that is kosher animals that have died of natural causes (such as disease or old age). So, technically it would be okay to use the skin of an animal that had died of natural causes, as long as it was a kosher animal, which also might satisfy the vegetarian or vegan practitioner.

However, a vegan who isn’t as attached to a traditional reading of Halakhah, and/or who decides to prioritise using non-animal materials, has more options for a scroll that isn’t made of animal skin. Avielah Barclay suggests a couple of approaches. Firstly, one could look at the original reason that animal skin likely became the choice material for Sofrut (Hebrew scribing) – durability. It was the longest-lasting material available at the time. The words of our sacred texts were considered too holy to be written on materials that would decompose quickly. Nowadays, we have other options for long-lasting scribal materials. Avielah says that she often works with vegetable parchment, which is made of cellulose, though she is very clear that she only does this for non-ST”M documents (Sifrei Torah, Tefillin and Mezuzot, that is, documents that legally need to be on animal skin), such as ketubot and other Jewish calligraphy pieces. Vegetable parchment looks very similar to animal parchment, but it’s made entirely of plant materials, and is apparently a pleasure for a scribe to write on, as it’s quite easy to write on with scribal ink.

Another approach Avielah suggests is looking at what other materials our ancestors have used to record our holy writings, since there are early precedents for scribing sacred texts in other ways. Although Avielah has never used non-traditional materials for ST”M documents, she says that she would be open to using other materials that our ancestors used for sacred texts (such as papyrus) before the Talmud’s standardisation. According to Sofer Marc Michaels, “In ancient times, a number of surfaces were normal for writing. Baked clay tablets…, walls of Temples and other administrative buildings, shreds of pottery, onto lintels and gates, engraved into metal…The Talmud even talks about whether writing a get (Jewish divorice document) on leaves still attached to the plant or the horn of a living animal is acceptable. However, the most common early writing surface for longer documents at the time the Torah text was being composed was actually papyrus” (Marc Michaels, ibid, p. 4). So with the exception of the horn of the living animal, that’s actually quite a lot of vegan materials to work with. If you take into account the practicalities of wearing tefillin, clay, metal or pottery shards might get a little heavy, but papyrus is about the weight of thick paper. Marc goes on to note that, “There are…a number of Biblical texts in the Dead Sea Scrolls that are written on papyrus” (Marc Michaels, ibid, p. 4).

Given my conversation with Avielah, I’d love to share a little about the vegan tefillin that I’ve commissioned her to make for me. While I don’t expect everyone to come to the same conclusions, I hope that by sharing this information, I’ll be empowering any vegans out there who want to take on the mitzvah of tefillin to make on their own choices. I’ve selected vegetable parchment as the material for the scrolls, with vegan gall ink for the letters. Having the tefillin custom-made means that Avielah will also be using a feminised text of the Shema prayer. For the straps, I’ve decided to use woven fabric, since weaving was a women’s sacred task in the ancient world; they’ll be embroidered with the names of my ancestors (mythic ones, as well as those from my family tree).

I am looking forward to being able to bind the prayers of my ancestors on my body in a way that feels true to my ethical outlook.

If you want to find out more about Avielah, you can visit her website and Facebook page.

*

Kohenet Yael Tischler is a ritual-weaver, Jewish educator and song leader. She is the co-founder of Yelala, a constellation of work that celebrates Earth-centred, feminist Jewish spirituality and reclaims the practices of our women/femme and folk ancestors. She holds an MA in Writing for Young People from Bath Spa University, a BA in English Literature from Columbia University and a BA in Tanakh (Bible) from the Jewish Theological Seminary.

Kohenet Yael Tischler is a ritual-weaver, Jewish educator and song leader. She is the co-founder of Yelala, a constellation of work that celebrates Earth-centred, feminist Jewish spirituality and reclaims the practices of our women/femme and folk ancestors. She holds an MA in Writing for Young People from Bath Spa University, a BA in English Literature from Columbia University and a BA in Tanakh (Bible) from the Jewish Theological Seminary.