When I served on the Cape Beth Din in South Africa, I had to join my colleagues in visiting the slaughterhouses and checking up on the shochtim. The kosher slaughterhouse in Cape Town was part of a general slaughterhouse complex enabling me to view the process of killing animals in both places. What I saw convinced me that while non-kosher slaughter was quicker and more “aesthetic” than kosher slaughter, it failed in its claim to be more compassionate in its methods.

In the non-kosher slaughterhouse, cows and sheep were herded at a rapid pace into the assembly line where electrodes hanging down from the ceiling were punched against their heads by a worker. (This was considered the most humane method of slaughter. Poleaxing is even more commonplace.) However it was plainly evident that the pace at which the animals were passing meant that the electrocution was only partially successful before many animals were strung up and painfully killed. The kosher slaughter was less rapid and the shochet gave “personal attention” to each cow or sheep, ensuring that his knife severed the trachea and esophagus with one swift gesture, making sure that the animal died immediately. I have no doubt that kosher slaughter is overwhelmingly more humane (even if less “aesthetic”) than the non-kosher method of slaughter and when I was Chief Rabbi of Ireland and responsible for all the kosher slaughter there, I became even more convinced of this.

However these experiences also introduced me to other factors involved in the livestock trade leading to slaughter; and over the years I became more and more aware of their implications

Modern factory farming involves not only quantities of livestock that had previously been unimaginable, but also conditions and treatment that in the past would have led religiously observant Jews to consider the consumption of such creatures as forbidden by Jewish law .

Some of the greatest halachic authorities of modern times such as Rabbi Moshe Feinstein and Rabbi Haim David Halevy, both of blessed memory, declared foie gras (goose liver produced by force feeding geese) and veal (the anemic flesh of a calf, denied light and movement) to be prohibited, as their production egregiously transgresses the Jewish prohibition of za’ar baalei hayim, causing cruelty to animals that is not essential for human consumption.

Now let’s leave alone for the moment the question of what is really necessary today for healthy living; these rabbis were simply stating the well-known fundamental Jewish teaching that prohibits the maltreatment of animals. However anyone familiar with the contemporary livestock trade will know that such animal maltreatment has become the norm.

Most cows for slaughter are kept and transported in severely restricted confines and their horns are cut or burnt off without any anesthetic to prevent them damaging one another in such confined areas. They are pumped with hormones and antibiotics that change their physiology and restrict their natural functioning.

One should also note that these hormones and antibiotics are retained in the flesh consumed by humans, with many negative consequences.

The situation is even worse for dairy cows. In order to induce maximal lactation which produces litres of milk for human consumption, calves are immediately taken away from their mothers (in direct contravention of the Biblical prohibition, Leviticus 22:27); and the hormones pumped into them enlarge their udders to such an extent that dairy cows are often incapable of walking.

An analysis by an American Orthodox halachic authority of the internal organs of dairy cow carcasses showed major organ distortions that would have rendered them treif, i.e. prohibited for Jewish consumption. This also has halachic ramifications regarding the milk of such treif cows.

Chickens in today’s factory farms grow three times as fast as they did fifty years ago as a result of selective breeding programs and the use of antibiotics. This leads to crippling bone disorders and spinal defects causing acute pain and difficulty in moving.

And as far as eggs are concerned – organic or otherwise – in order to guarantee maximal production, male chicks are killed after birth, thrown alive into grinders or suffocated in bags.

Enough of the horror stories! It should be evident to anyone with eyes in his or her head that virtually all animal products on the market today are the result of practices that categorically contravene Jewish law and ethics. And even if eating these products is considered a halachic obligation (which is not the case), under these conditions it would be a mitzvah habaah baveirah, the product of illegitimate means which disqualifies the ends.

It should be clear that the rationales of Rabbi Moshe Feinstein and Rabbi Hayim David Halevi are not just relevant today to foie gras and veal, but apply across the livestock/animal food production industries.

Kashrut involves more than just the way the animal‘s throat is cut and the checking of its vital organs. Kashrut involves the whole relationship between humans and the animal world. Indeed our sages say specifically in relation to shechitah that “the mitzvot were only given in order to refine people” (Genesis Rabbah, 34; Leviticus Rabbah, 13.)

If at point Z the animal’s throat was cut the right way and its internal organs checked, but from A to Y all injunctions and prohibitions have been ignored and desecrated, how can that product really be called kosher?

Why is there virtually no official rabbinic dissent let alone opposition to such practices?

Some of it is due to ignorance, but most of all these facts are uncomfortable and it is much easier to avoid or deny them. But might it not also have to do with the fact that the kosher food industry, and all the rabbinic supervision and authorization inextricably bound up with it, constitutes an enormous industry relating to the livelihoods, interests and power of myriads of people? One wonders whether it is even possible to stop the train of this enormous immoral enterprise where both legitimate and not so legitimate interests are so inextricably intertwined.

Modern technology and innovation, which currently compound the evil, may eventually offer us ways out of this imbroglio. Nevertheless, in the meantime if not for longer, responsible rabbinic leadership should be advocating a plant based diet as much as possible, as the most kosher diet available for most people today.

It is perfectly feasible in our modern world to obtain full nutrients for a healthy body without needing to be party to such immorality. And all this is not to mention other ethical issues, such as greater and more equitable distribution of food resources, and the environmental damage done by the livestock trade (which is greater than all the forms of transport in the world put together. See “Livestock’s Dark Shadow” issued by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.)

Of course there were great rabbis such as Rabbi Avraham HaCohen Kook and before him Rabbi Yosef Albo and others, who envisioned a messianic age in which there is no killing of animals (and which will even be reflected in the Temple service itself). But even if you are not attracted to such visions, in today’s modern world the more one’s diet is plant based the more one is truly keeping kosher.

Written by Rabbi David Rosen for the Times of Israel.

—

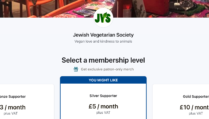

Rabbi David Rosen served as the senior rabbi of the largest Orthodox Jewish congregation in South Africa, and as Chief Rabbi of Ireland. He is currently the American Jewish Committees International Director of Interreligious Affairs, based in Jerusalem. He is also a Patron of the Jewish Vegetarian Society.