The mass murder of male chicks and trimming of females’ beaks are standard practice in factory farming. Consumers must say no to these anachronisms, writes Chas Newkey-Burden for the Guardian.

From the moment it hatches, a baby chick’s fate is determined by its gender. Females are seized and have the tips of their sensitive beaks cut without anaesthetic. Males are sent to be killed. These are commonplace practices on British farms, including free-range ones. They are some of the simple truths the industry doesn’t want you to know.

Factory farm practices have become so horrific that high walls have been built, not only literally but metaphorically too. Expert marketers are deliberately misleading consumers. Perhaps their most audacious trick is the “free-range” brand label that persuades many well-meaning shoppers to pay extra because they believe those eggs will come from a natural environment. The truth can be very different.

A harrowing report published today by Viva, a vegan charity campaigning to end animal suffering, blows the fantasy apart. The charity’s year-long investigation, including undercover work, found hens living in heartbreaking conditions. Imagine thousands of birds crammed into a dirty shed, only existing so their eggs can be taken and sold for profit. Even some farms that boast a “high welfare” label were described in the report in terms of squalid hellholes.

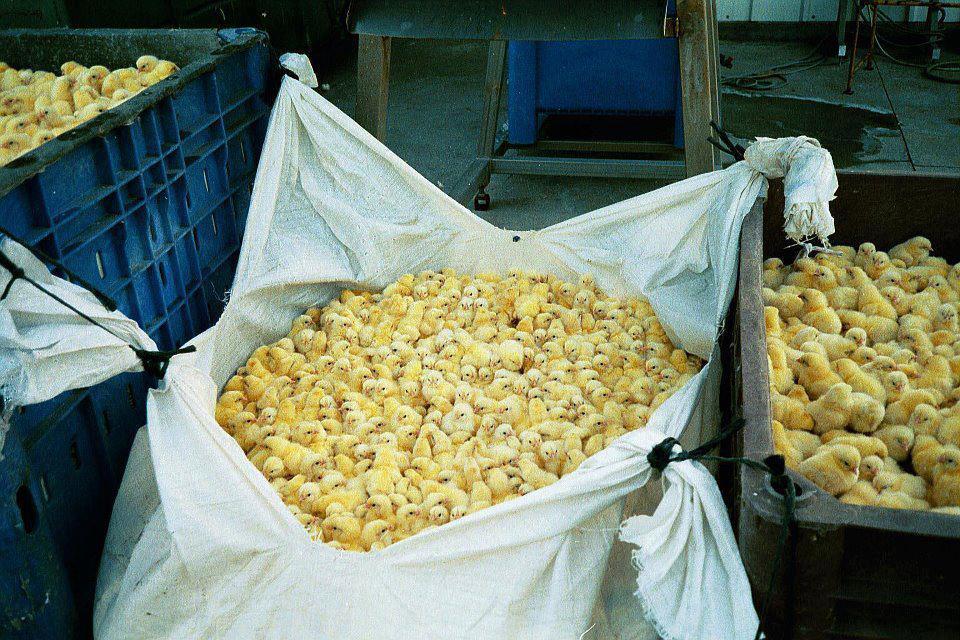

The Viva report comes at a vulnerable time for the industry. Many of us were moved by the recent news of 1,800 newborn chicks found dumped in a field in Lincolnshire. The scene was described as a “sea of yellow” as the stressed chicks huddled together. “I’m never going to get over the number and the vulnerability of these particular animals,” said an RSCPA inspector, who has witnessed plenty of horrific things in his work.

The story tugged at the heartstrings of a nation, but few who were moved by that extraordinary incident are aware of the routine wickedness that surrounds everyday egg production: 40m male chicks are killed every year, deemed useless and worthless by the industry. Denied water and food, they are gassed with carbon dioxide after just a day or two of life.

This is the industry standard in Britain but Viva found that two-thirds of British people were unaware of it. Once they knew, 69% thought the practice should be outlawed. Other countries are making progress. United Egg Producers, the organisation that sells 95% of eggs produced in America, says it will eliminate the practice by 2020. Similar commitments have been made in Germany, Australia and Canada.

European scientists have developed a technology called in-ovo sexing, in which chemical biomarkers are analysed to determine the sex of a chick on the ninth day of incubation. Future male chicks can then be aborted in their shells before they develop and hatch. But the British industry says profit must come first. A spokesman for Noble Foods, one of the top two producers in the UK, says in-ovo sexing “dramatically reduces egg hatchability and the viability of using the technique on a commercial level”. He adds: “I don’t think it’s going to be a viable option soon.”

The industry has also fought off efforts to end beak trimming, which it uses to stop hens pecking at each other. Pecking is a natural response to being kept in unnaturally large, cramped and traumatised flocks. A ban was due to come into force in 2011, but lobbyists persuaded the coalition government to postpone the change and it keeps being postponed.

Organic farms certified by the Soil Association have already banned beak trimming. They also offer more space per hen, and restrict the use of antibiotics, but the fate of their male chicks is the same as the rest of the industry.

In any case, very few people buy organic: of the 12.2bn eggs sold in the UK in 2015, just 2% were organic. And while beak trimming must be eliminated, so must the heartlessly cramped conditions which make mainstream farmers feel it’s a necessary protection.

The only way these practices can continue is if the public remains ignorant. As long as people are kept in the dark, there will be little pressure on the government to ban either the mass murder of male chicks or the mutilation of female beaks. Both practices are anachronisms, justifiable only if you value money more than anything else.

Farm animals are at the epicentre of the view that some lives are more valuable than others and that the powerful are entitled to exploit the powerless. But if you invest in this view at the supermarket checkout, you can’t expect to never be subject to it yourself.

So don’t be taken in by talk of contented hens or those drawings of cute, imaginary farmyards on the egg boxes. Look instead at a true picture: a conveyor belt carrying day-old chicks to their respective fates – males sent to one side to be gassed, females to the other side to be squeezed into dark sheds, exploited for as long as they’re profitable until their own day of slaughter comes.

The process shames the industry but it also shames all who look the other way. It’s nearly impossible to make an omelette without participating in practices you may not like. Unlike the chicks, we can make a choice. Will you keep buying eggs or not?