By Yonassan Gershom and Richard Schwartz

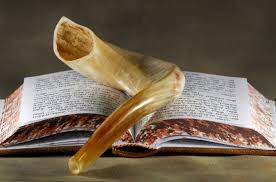

Every year, before Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), some Jews perform the ceremony of kapparot. The following, in question and answer format, is a discussion of the ritual and its relation to the treatment of animals.

What is kapparot [in Ashkenazic Hebrew or Yiddish, kapporos or shluggen kapporos]?

Kapparot is a custom in which the sins of a person are symbolically transferred to a fowl (or a substitute object—as discussed below). First, selections from Isaiah 11:9, Psalms 107:10, 14, and 17-21, and Job 33:23-24 are recited; then a rooster (for a male) or a hen (for a female) is held above the person’s head and moved (1) in a circle three times, while the following is spoken: “This is my exchange, my substitute, my atonement; this rooster (or hen) shall go to its death, but I shall go to a good, long life, and to peace.” The hope is that the fowl, which is then donated to the poor for food, will expiate the sins of the person who takes part in the ritual, and thereby avert any punishment or misfortune.

What is the history of this rite?

Kapparot is not mentioned in the Torah or in the Talmud. A possible forerunner is mentioned by Rashi (a tenth century scholar) in his commentary to the Talmud (Shabbat 81b), where he describes a custom of waving a potted seedling over one’s head seven times and then throwing it into the river before Rosh Hashanah (Jewish New Year) as an atonement. This was done with a prayer very similar to the one now used for kapparot before Yom Kippur, and indicates that such ceremonies did not always employ with a fowl.

Jewish scholars first discuss the custom of doing kapparot with chickens in the ninth century. They explain that since the Hebrew word gever means both “man” and “rooster,” punishment of the bird can be substituted for that of a person.

However, according to the Encyclopedia Judaica (Volume 10, pages 756-757), several prominent Jewish scholars strongly opposed kapparot during the Middle Ages. Rabbi Solomon ben Abraham Aderet, one of the foremost Jewish scholars of the 13th century, considered it a heathen superstition. This opinion was shared by the Ramban (Nachmanides) and Rabbi Joseph Caro, the major codifier of Jewish law, who called it “a foolish custom” that Jews should avoid. These rabbis all felt that kapparot was a pagan custom that had mistakenly made its way into Jewish practice, perhaps because when Jews lived among pagans this rite seemed like a korban (sacrifice) to some extent.

On the other hand, the Kabbalists (led by mystics such as Rabbi Isaac Luria and Rabbi Isaiah Horowitz) perceived in this custom a mystical significance. Rabbi Moshe Isserlis (the major 16th century scholar, known as the RaMA), whose interpretations of the Shulchan Arukh (Code of Jewish Law) are authoritative for Jews of Eastern European descent, also endorsed the custom of kapparot as valid and proper. This greatly enhanced the popularity of the kapparot ritual down to the present day. The Baal Shem Tov, founder of Hasidism, also practiced kapparot, and most Hasidic communities are still in favor of keeping the custom as part of their traditions. Some Jews also feel that, although this is not officially a sacrifice, it keeps the concept of sacrifice alive in preparation for the rebuilding of the Temple.

Why did some Jewish commentators oppose kapparot?

Some Jewish leaders felt that people would misunderstand the significance of the ritual. The belief that the ceremony of kapparot can transfer a person’s sins to a bird, and that his or her sins would then be completely eradicated, is contrary to Jewish teachings. If the ritual could remove a person’s sins, what would be the need for Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement? What would be the need for soul-searching and repentance?

The Mishnah Brurah, a major early 20th century commentary on Rabbi Joseph Caro’s classical Code of Jewish law, written by the respected Chofetz Chaim at the beginning of the 20th century, explains the significance of the ritual. Although he does not forbid it outrightly, the Chofetz Chaim stressed that a person cannot obtain purity from sin, and thus obtain higher levels of perfection, without repenting. Through God’s mercy, we are given the Divine gift of repentance, so that we might abandon our corrupt ways, thereby being spared from the death that we deserve for our violation of the Divine law. The Chofetz Chaim concedes that by substituting the death of a fowl, one may (hopefully) be reminded of one’s mortality and appreciate God’s mercy in not killing us for our sins, and thereby be stirred to repentance. By no means, however, do the ritual and the slaughter of the bird itself eradicate one’s misdeeds, even though the bird is donated to the poor.

The following statement by Rabbi David Rosen, former Chief Rabbi of Ireland, provides additional sources for the case against the use of chickens for kapparot:

Beyond the objections of the Ramban, Rashba and the Bet Yosef, to the custom of “kapparot” and beyond the warnings of rabbinic authorities such as the Chayei Adam, Kaf HaChaim, Aruch HaShulchan and the Mishnah Brurah regarding the halachic infringements involved in using live fowl for this custom, the latter also desecrates the prohibition against “tsa’ar ba’alei chayim” (causing cruelty to animals).

What are more recent objections to this ceremony?

In the past, when Jews lived in rural areas and raised their own chickens, it was a very simple matter to choose a hen or rooster from a local flock to be eaten for the pre-Yom Kippur meal. In fact, the Shulchan Arukh says not to specifically seek out a white chicken (in reference to Isaiah 1:18) or pay more for it than usual for the pre-fast meal, because this resembles the superstitions of the pagans (darchei ha-Emori). (2) Instead, people should use whatever chickens they already have on hand, the same as for any other meal. Nowadays, however, most Jews are urban and nobody has his or her own chickens, white or otherwise. Today’s chickens used for kapparot are all white, factory-farmed birds(3) brought in specifically for the ritual, and often cost more than a chicken at the grocery. One could therefore argue that everyone is “seeking out a white chicken” and that the ritual has become a superstitious practice.

Because modern kapparot chickens are trucked into the city from long distances, often in open trucks exposed to the weather and without adequate food or water, the question of tsa’ar ba’alei chaim (cruelty to animals) has become an important issue. The birds may also suffer while they are being handled for sale or during the ceremony, because many urban Jews are unfamiliar with the proper, humane way to hold a chicken. (Which should be with a hand above and one below the bird, supporting the weight of the body, not held with the wings painfully pinned back, as is done at some kapparot centers.)(4) In some places in Israel and the United States, chickens are sold on street corners for this ceremony, and not every merchant takes proper care of his chickens during this period. The birds are frequently cooped up in baskets, and some merchants neglect to give them sufficient food or water. In some cases, the caged chickens have been left out in the rain or under the hot sun with no shade or shelter, or simply abandoned in warehouses and left to starve if not sold in time for the ceremony.

Although Rabbi Isaac Luria supported this ritual in his day, he was also against the unnecessary suffering of animals. In Shivchei Ha-Ari, there appears the story of the Ari telling a student that he had lost his place in the World to Come for failing to feed and water his chickens properly. The cries of those suffering chickens were canceling out all the prayers and Torah learning of that student. This is based on the general principle that one cannot commit a sin—in this case, cruelty to animals—in order to do a mitzvah.

There is also the additional problem, already raised in the Shulchan Arukh in the 16th century, of animals experiencing fear during slaughtering from seeing other animals slaughtered in front of them, which is forbidden. This fear can even cause the lungs to shrivel and render the meat not kosher. (Shulchan Arukh Yoreh Deah 36:14) The Yad Ephraim, commenting on this ruling, refers specifically to the problem of many people standing in line side-by-side with fowl to be slaughtered for kapparot, saying, “And this [slaughtering of one bird in the sight of another] is not correct for this is a violation of tsa’ar ba’alei chaim… and there is no greater infraction of animal cruelty than this. And we do not say that fowl do not have feelings, for behold it was just described that sometimes their lung is shriveled due to the sight of slaughter before them.” (Yad Ephraim, Yoreh Deah 34:14)(5)

In more recent times, the renowned Haredi kabbalist Rabbi Yitzchak Kadouri (died in 2006) writes that one should abstain from using chickens for kapparot due to “the cruelty to animals, which is prohibited by the Torah, and kashrut problems.” For those reasons, Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach (1910-1995), a leading authority on Jewish law and head of the Kol Torah yeshiva in Jerusalem, also stopped using animals for kapparot, giving charity instead.

In addition, it should be noted that in some recent cases in New York City, the meat was not actually given to the poor, but simply discarded in the trash at the site of the ceremony, because there was no time to properly kasher and distribute it. This is a violation of bal tashchit, the principle that we should not waste or needlessly destroy things. Again, one cannot do a sin in order to fulfill a mitzvah.

So we must ask ourselves, what is the spiritual impact of this ceremony in modern times? Does the suffering of the chickens outweigh any benefit that might be derived from it? While the Jewish tradition is filled with concepts, prayers, and actions during the Rosh Hashanah-Yom Kippur period that are designed to emphasize the importance of rachamim (compassion and sensitivity), the message of kapparot to those who take part and those who watch it (including children) may be just the opposite. In some cases, they may learn a lesson of insensitivity to the suffering and feelings of other living creatures.

How should Jews who are concerned about the treatment of animals respond to this issue?

Jews who are concerned about the treatment of animals should try to engage courteously and respectfully with Jews who perform kapparot using chickens. It should be recognized that they are performing what they regard as an important religious act. Shouting slogans like “meat is murder” or accusing them of being “barbaric” or “medieval” will be ineffective and will only serve to arouse hostility. Traditional communities resent “outsiders” telling them what is “wrong” with their cultures. In order to have a dialogue with religious people, one must be willing to meet them respectfully within the context of their own worldview. Here are some of the points that might be respectfully brought up:

1. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, Rashi cites a kapparot-type ceremony where a plant was used instead of an animal, indicating that it is not “written in stone” to slaughter a chicken. Today, there is another substitute kapparot ceremony that is widely practiced by many Torah-observant Jews. Money, perhaps equal to the monetary value of the fowl, is substituted for the rooster or hen. The money is put into a handkerchief which the person swings three times around his or her head while reciting a modified version of the prayer: “This money shall go to charity, and I shall go to a good, long life, and to peace.” This is based on the statement in the Torah that people who lived too far from Jerusalem to bring their tithes in animals or produce could “turn it into money” and bring that instead. (Deut. 14:24-26) By substituting money for a fowl in kapparot, the heightened sense of repentance can be kept, and perhaps even enhanced, since no bird has to lose its life or suffer for our sake. This substitution, which maintains the tradition of giving charity (the substituted money) to the poor, has been endorsed by many rabbis and is mentioned in many prayer books, including the Artscroll Siddur, used in many Orthodox synagogues.

2. We should attempt to increase the knowledge of Jews with regard to Judaism’s beautiful and powerful teachings with regard to showing compassion to animals. The following are a few examples:

• Moshe Rabbenu, (our great teacher, Moses) and King David were considered worthy to be leaders of the Jewish people because of their compassionate treatment of animals, when they were shepherds. Rebecca was judged suitable to be a wife of the patriarch Isaac because of her kindness in watering the ten camels of Abraham’s servant Eliezer.

• Many Torah laws involve proper treatment of animals. One may not muzzle an ox while it is working in the field nor yoke a strong and a weak animal together. Animals, as well as people, must be permitted to rest on the Sabbath day. The importance of this Sabbath rest for animals as well as people is indicated by the fact that it is included in the Ten Commandments. Jews also recite it every Sabbath morning as part of the Kiddush ceremony.

• The psalmist indicates God’s concern for animals, for “His compassion is over all of His creatures” (Psalms 145:9). And there is a mitzvah-precept in the Torah to emulate the Divine compassion, as it is written: “And you shall walk in His ways” (Deuteronomy 28:9). Perhaps Proverbs 12:10 best summarizes the Jewish attitude toward animals: “The righteous person considers the soul (life) of his or her animal.” In summary, the Torah prohibits Jews from causing tsa’ar ba’alei chaim, any unnecessary pain to living creatures, even psychological pain. This principle is based on the Torah itself, and takes precedence over rabbinical decrees or folk customs.

• Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, an outstanding 19th century philosopher, author, and Torah commentator, eloquently summarizes the Jewish view on treatment of animals: “Here you are faced with God’s teaching, which obliges you not only to refrain from inflicting unnecessary pain on any animal, but to help and, when you can, to lessen the pain whenever you see an animal suffering, even through no fault of yours.” (Horeb, Chapter 60, #416)

3. Based on the enormous weight of Biblical, Talmudic, medieval, and modern sources commanding the prevention of animal suffering, it can be argued that one way that Jews can accomplish repentance and other goals of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur is by moving away from the unnecessary exploitation of animals. Many of the observances and values of this holiday period are more consistent with practicing mercy toward all of God’s creatures:

* Prayers on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur for God’s compassion during the coming year are most consistent with acts of kindness to both other people and animals. This story reinforces that idea: Rabbi Israel Salanter, one of the most distinguished Orthodox Rabbis of the nineteenth century, failed to appear one Yom Kippur eve to chant the sacred Kol Nidre Prayer. His congregation became concerned, for it was inconceivable that their saintly rabbi would be late or absent on this very holy day. They sent out a search party to look for him. After much time, their rabbi was found in the barn of a Christian neighbor. On his way to the synagogue, Rabbi Salanter had come upon one of his neighbor’s calves, lost and tangled in the brush. Seeing that the animal was in distress, he freed it and led it home through many fields and over many hills. This act of mercy represented the rabbi’s prayers on that Yom Kippur evening.

* Consistent with Rosh Hashanah as a time when Jews are to “awaken from slumber” and mend our ways, using money for the kapparot ritual shows that we are putting Torah teachings about compassion into practice.

* Acts of kindness and charity are consistent with God’s “delighting in life” on Rosh Hashanah, since, unlike the kapparot ceremony using chickens, they don’t involve the potentially cruel treatment and death of animals.

4. Finally, we should remind others that kapparot is not Biblically or Talmudically ordained (as is tsa’ar ba’alei chaim), that the custom arose at a later period in Jewish history, that it has been rejected by many Jewish sages, and that the important goal of increasing our sensitivity to the importance of repentance and charity can be accomplished as well, and perhaps better, by substituting money for a bird. As rabbi David Rosen, former Chief Rabbi of Ireland, puts it:

Those who wish to fulfill this custom can do so fully and indeed in a far more halachically acceptable manner by using money as a substitute, as proposed by many Jewish authorities.

Richard H. Schwartz

Professor Emeritus, College of Staten Island

Author of Judaism and Vegetarianism, Judaism and Global Survival and Mathematics and Global Survival and over 140 articles at JewishVeg.com/schwartz

President. Jewish Vegetarians of North America (www.JewishVeg.com); Director of Veg Climate Alliance

Associate producer of A SACRED DUTY

[email protected]

“Like” JVNA on Facebook at facebook.com/JewishVeg