By Felicity Lawrence, Andrew Wasley and Radu Ciorniciuc (Wednesday 23rd July 2014)

Three of the UK’s leading supermarkets have launched emergency investigations into their chicken supplies after a Guardian investigation uncovered a catalogue of alleged hygiene failings in the poultry industry.

Undercover footage, photographic evidence and information from whistleblowers has revealed how strict industry hygiene standards to prevent the contamination of chicken with the potentially deadly campylobacter bug can be flouted on the factory floor and on farms.

Specific incidents identified in the last month include a factory floor flooded with chickens guts in which the bacteria can flourish, carcasses coming into contact with workers’ boots then returned to the production line and other poor practices involving points in the production chain that increase the risk of its spread.

The evidence prompted Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Marks & Spencer to launch emergency investigations into their chicken sources over the last week.

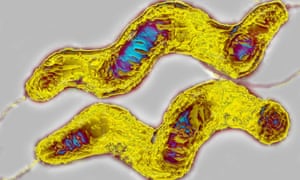

The concern centres on the bacteria campylobacter, which at the last count was present in two-thirds of British fresh chicken sold in the UK. Although the bug is killed by thorough cooking, around 280,000 people in the UK are currently made ill each year by it and 100 people are thought to die. Contamination rates are known to have increased in the past decade.

The Food Standards Agency (FSA), however, decided on Wednesday to shelve a promise to name and shame supermarkets and processors for their campylobacter rates. The climbdown comes after “push-back” from industry and interventions from government departments.

One source said they had been told Number 10 had raised concerns about the communication of the results, fearing that they could provoke a food scare similar to that triggered when the former Conservative minister Edwina Currie warned that most of British eggs were contaminated with salmonella in 1988.

The Guardian’s five-month investigation uncovered a series of alleged hygiene failings in the chicken industry.

The allegations have been made against two of the largest UK poultry processors, 2 Sisters Food Group and Faccenda. They relate to two factories owned by 2 Sisters that supply fresh chicken and chicken for ready meals to Tesco, Asda, Sainsbury’s, Aldi, M&S, KFC and to farms and an abattoir owned by Faccenda, which supplies Asda and Nando’s.

The allegations are that:

• Chickens which fall on to the floor have repeatedly been put back on to the production line at two 2 Sisters sites. They company denies this ever happens and says all chicken from the floor is correctly disposed of as waste.

• Breakdowns led to high-risk material – feathers, guts and offal – piling up for hours on separate occasions while production continued at a 2 Sisters factory in Wales. The company says they did not stop the line because they had to consider the welfare of chickens waiting in crates to be killed.

• Another breakdown led to the water in scald tanks at the same site not being cleaned for three days, so that around 250,000 birds passed through dirty water after slaughter. The company says this was an isolated incident that lasted only one day, bacteria counts were checked and were acceptable.

• According to a whistleblower chicken catcher, biosecurity rules to stop the spread of campylobacter in chicken sheds at Faccenda were regularly ignored by workers when he was employed there. Faccenda says this is not true and it has invested heavily in a highly trained and motivated workforce.

Campylobacter contamination has plagued the poultry industry for more than a decade and has got worse in that time.

The FSA ordered new tests for campylobacter amid worries that there had been no improvements in rates. Results were due in June, and as recently as March the FSA’s chief executive, Catherine Brown, publicly vowed to press ahead with “steely determination” despite push-back from industry.

On Wednesday, however, Brown asked the FSA board to reverse the previous decision to publish campylobacter results for named supermarkets and processors every quarter. The board heard that there were now concerns, not raised previously, that the sample size for one quarter’s data was insufficiently large to be statistically robust.

Brown insisted that the threat of exposing campylobacter results had made supermarkets and chicken processors take notice of the FSA’s concerns about contamination for the first time, but said the industry had not so far made the changes in production needed to reduce campylobacter on any scale.

“Time is upon us for everyone to work out how they are going to stump up money to make the interventions on [the production] line,” she told the meeting.

The eight members of the board were divided on the proposals, leaving the chairman and former president of the National Farmers’ Union, Tim Bennett, to use his casting vote to quash the plans to name companies for the moment. They are looking at separate proposals to urgently increase the testing of retail chicken.

Steve Wearne, director of policy at the FSA, said ahead of the board meeting: “Other government departments have reflected to us concerns which are the same as those we’ve heard directly from retailers and producers. We’re not letting the industry off the hook. We’ll publish all the names when we’ve completed [the survey] next summer.

“If we publish the results piecemeal, other people might draw unwarranted conclusions from partial data and we don’t want consumers being misled or confused.”

Erik Millstone, a food safety professor at Sussex University, condemned the board’s decision. “In the last few years the Food Standards Agency has been under a great deal of pressure from the government and the food industry to ensure that it only provides reassuring messages, and especially that it should say nothing that could provoke any ‘food scares’,” he said. “But the FSA was created to protect consumers, not to protect the food industry, or to give ministers a quiet time. This decision shows that its independence is entirely illusory.”

The executive director of Which?, Richard Lloyd, said: “The Guardian’s investigation raises serious concerns. Tackling campylobacter has to become a much bigger priority for supermarkets and their suppliers as it is responsible for thousands of cases of food poisoning and the deaths of 100 people every year. It’s therefore disappointing that the FSA has gone back on its commitment to publish in full the quarterly data on the levels of campylobacter in supermarket chickens, when it is clearly in the public interest to do so. The FSA must put consumers first and operate more transparently than this.”

The campylobacter story

Although the public are mostly unaware of it, the scale of campylobacter contamination and the number of people it makes ill each year have been well-known among industry bosses, retail directors and government officials for more than a decade. The annual cost to the economy is a staggering £900m, making a significant dent in the £3.3bn the poultry industry claims to contribute to Britain’s GDP. Up to 80% of campylobacter infections are attributable to contaminated poultry.

The points in the chicken production chain at which contamination occurs are clearly understood, but during the past decade the picture has got worse. In 2003 the FSA reported that 56% of chicken on sale was infected. By 2008 that had increased to 65%.

The decision over whether to name and shame the industry is a vexed one. The stakes are high – consumers are likely to shun poultry in supermarkets with the worst scores. Cleaning up would require money, experts say, and poultry firms and retailers are locked in to an economic structure of their own making in their race to produce the cheapest possible chicken.

In the factory

The Guardian has investigated the weak links in the chicken chain, gathering material from undercover film, photographic evidence and whistleblowers.

Just last month – on a not untypical day, according to sources – at a vast chicken abattoir in Anglesey owned by the UK’s largest poultry company, 2 Sisters Food Group, something of the nature of the problem is revealed. Tesco, M&S and Asda are among the customers for chicken for ready meals supplied from this site.

The pump system has broken down again, and the channel that is supposed to drain away the innards from the tens of thousands of chickens killed and processed each day for supermarket orders has been blocked for a prolonged period. Guts and offal extracted during a process called evisceration are piling up to form a gory heap of high-risk material. The floor around is wet with blood. Campylobacter is carried in the guts and faeces of chickens and evisceration is one of the key points in the processing chain at which contamination occurs.

“That’s unbelievable, it just shouldn’t be allowed to happen,” said Ron Spellman, the director general of EWFC, which represents meat inspectors across the EU, when we showed him pictures the Guardian had obtained of the incident that had been described to us. Spellman was a poultry inspector for 12 years.

“They should stop the line and clean up. But that costs money, and the process is generally run so hard and fast, if a line is down too long they don’t have enough hours in the day to fulfil their supermarket orders. And if they don’t meet orders, they lose the contract.”

In Spellman’s view, the driving down of prices is a key part of the problem. “The supermarkets have got to have some responsibility because they push harder and harder on price. There is this perception that supermarkets somehow keep the industry honest and hygienic, but what we’ve seen is that it doesn’t work,” he said.

Modern poultry processing is a production line business. Birds are hung upside down on a moving conveyor belt of shackles at the beginning of the abattoir, and in a sort of food Fordism, carried seamlessly through every stage from slaughter to washing, chilling, cutting and packing at high speeds. Large abattoirs typically run lines at a rate of 185 to 195 birds a minute, or nearly 12,000 an hour.

On the evisceration line, guts are scooped out by automated metal fists. Today’s chickens are bred to fatten fast to a standard 4lb (1.8kg) size in six weeks, but as units of production they are not as obligingly uniform as car parts. If the machine is not adjusted to different crops of birds as they come through, the metal fist can burst the guts, and then any campylobacter is automatically spread to bird after bird. Adjusting machinery or stopping the line to clean up takes time and costs money.

On a separate occasion last month in the same factory, workers witnessed another breakdown. Workers say these are repeated events. This time it was the pump feeding the flume of water that is supposed to carry feathers away from the plucking machines.

The defeathering machines are another high-risk point for campylobacter infection. Slaughtered birds pass first through a scald tank of warm water to loosen the feathers and then through a series of whirring rubber fingers which pull the feathers out. The feathers themselves can be contaminated with faeces, the fingers put pressure on the birds and can squeeze out more faecal matter, and the fingers can become impregnated with bacteria.

In the steamy atmosphere, campylobacter from the feathers can also become airborne. Removing the feathers promptly through the drains is a vital part of food safety, but the evidence provided to us suggests they had piled up for hours as production was allowed to continue at the Anglesey site.

Across the industry, the water in the scald tank is generally only changed once a day, so that by the end of a shift it can become a soup of chicken faeces and dirt. This used to be a high-risk point, but the water is now kept hot enough to kill bacteria. The foam that forms on the top, however, is cooler and bacteria can survive here, according to Spellman, with each bird passing through it as it goes on its way.

At the Anglesey plant, sources told us of an occasion last month when there was another breakdown. They said the scald tank was left uncleaned for two nights, so that three days of fresh birds – more than 250,000 chickens – were processed through the same dirty water.

Our sources told us that managers were made aware of these different breakdowns, but said the lines must be kept running because they had to meet targets.

We asked 2 Sisters why the lines had not been stopped for cleaning when these incidents occurred. The company told us that it and the vets had to make difficult decisions when there were breakdowns in the evisceration, defeathering and scald tank parts of the line. These required weighing up contamination risk with the welfare of chickens waiting in crates to be slaughtered.

The company denied that the scald tank had gone uncleaned over three days of production, saying it was an isolated incident which lasted only a day, and that it had tested for bacteria counts at the time and found they were acceptable.

2 Sisters bought the Anglesey factory last year when it acquired the UK operations of the Dutch poultry group Vion. Despite being one of the largest meat processors in Europe, Vion had decided to leave the UK market altogether after years of extremely tough trading conditions.

The industry runs on slim margins from the retailers and main fast food companies. Making a profit depends on being able to process very large volumes. That has driven not just the speed of production but also the concentration of ownership. Just four companies account for most of the UK market.

The alleged repeated breakdown of good hygiene at Anglesey appears dramatic, but our investigation has found problems elsewhere that help account for the rate of campylobacter on our chicken.

We had been told by insider sources in several different factories that one reason campylobacter rates remain stubbornly high was that across the industry there was a gap between companies’ policies on good hygiene and auditing systems to check for it, and the reality on the factory floor during long shifts and intense production.

Our reporter went undercover to look for a job in a chicken factory to find out what it was really like. He found one at another 2 Sisters poultry factory in Scunthorpe. This site supplies Tesco, Sainsbury’s, KFC and Aldi among others.

He witnessed carcasses with traces of faecal contamination that had made it through to packing for sale. Insider sources with expertise in food safety have told us this is common across the industry and is even unavoidable given the way chicken is processed. 2 Sisters said this allegation did not “reflect reality” and that the company had strict controls on carcass contamination which would remove them from the food chain.

Workers are trained to bin any meat that falls on the floor, where it could be contaminated, but our reporter saw staff pick it up and recycle it in to the production line on repeated occasions when preparing orders.

In one episode of almost grotesque comedy, a carcass that had fallen on the floor was run over by a worker pushing a trolley of crates, before our reporter saw it eventually being scooped up and lobbed back into production by a supervisor who then wipes their hands on their coat rather than washing them. We do not know where the chicken ended up. He was told it was going to Birmingham, where the company has another plant that debones chickens and processes them.

Jamie Pritchard worked as a meat cutter at 2 Sisters’s Anglesey site last year before leaving to join another meat company. He says during his time there he too saw workers picking chickens off the floor and putting them back in to production instead of throwing them into the waste bins. When auditors were present, he said, this never happened and line speeds were slowed down.

“If there’d be a site audit everything would be absolutely perfect, the line would be running at the correct speed. The carcasses would be clean, there’d be no faeces inside, but on the days when there wasn’t an audit, things would pile up and drop on the floor. If there was a visitor, you’d be told to put them in the bin ‘for not fit for human consumption’. But on days when there wasn’t an audit, basically, just wipe it down and put it back on the line.”

Reviewing footage of the incidents at Scunthorpe for us, Spellman said they were unacceptable. Those incidents, he said, suggests a culture in the factory that does not care that it is producing human food.

2 Sisters denied this could have happened. The company said it had stringent procedures for handling meat that falls on the floor, and only a team of trained waste operatives is authorised to handle it so that it never goes for human consumption. In a statement, the company said: “The allegations about our processing sites at Scunthorpe and Llangefni [Anglesey] are untrue, misleading and inaccurate. Both sites have British Retail Consortium ‘A’ grade Food Standards certifications, based on a number of announced and unannounced visits. In addition, we and our customers carry out a number of audits of our operations. None of these audits have uncovered any concerns about our hygiene standards or food safety.

“Our Scunthorpe site has already surpassed the FSA’s 2013 targets to reduce campylobacter levels, and continues to work towards the 2015 target. We [have been] praised as sector-leading by the FSA .”

We asked the company what its campylobacter results were. It said that 61% of the Scunthorpe chickens in the FSA survey tested positive for campylobacter. It added that 37% were contaminated in the middle range of bacteria levels and 2% were heavily contaminated. Across the company, 19% of 2 Sisters chickens were heavily contaminated, its director of communications, Nick Murray, told us.

On the farm

The trouble with campylobacter starts even earlier in the chain. One of the key risk points is on the farm.

Standard chickens are raised in large-scale industrial farms where as many as 40,000 birds may be reared at a time in “crops” that take around 42 days to reach slaughter weight. To maximise return on capital invested in floor space, it is common practice to overstock sheds with chicks at the beginning of the cycle and then send in teams of catchers to thin out some of the birds so that the rest of the chickens have just enough room to meet regulations on stocking densities as they grow to full slaughter weight. Each bird has less floor space than the size of an A4 sheet of paper.

When teams of chicken catchers go from farm to farm and enter the sheds, there is a high risk of cross contamination and flocks being colonised with campylobacter.

Strict rules on biosecurity are supposed to reduce the risk, and extra measures have been introduced in the last couple of years. By the end of 2013, however, they had had little impact, according to an FSA report. It suspected from research that they were not being followed consistently by producers.

Paul Sadler was employed by Faccenda, another of the UK’s largest poultry suppliers whose customers include Asda and Nando’s. Sadler worked there as a chicken catcher for almost 15 years until he left last year.

Sadler claims that supposedly strict processes were flawed and frequently flouted.

“As far as biosecurity [goes], they used to pay lip service, the emphasis [being] on trying to demonstrate that they complied with the legislation or good practice rather then actually following it. For example, they would have disinfectant baths outside each shed, which in principle, each catcher would dip their boots in before going from one shed to another. The problem was that baths were there and no one really used them.”

The Guardian has obtained internal Faccenda documents highlighting how the supply of birds can exceed capacity at the abattoir and how some end up stored in crates overnight. The FSA has identified stress during transport in crates as a danger point for campylobacter spread because the birds defecate more, spreading the bacteria.

Faccenda says it never plans to do this but has left birds overnight on 11 occasions this year because of mechanical problems. The chickens were, however, slaughtered within the regulation 12-hour maximum, the firm said.

Faccenda told us that the allegations about biosecurity lapses were untrue and that it had invested heavily in good wages and training to make sure staff were highly motivated to follow the rules. It added that it was playing a leading role in tackling campylobacter, working closely with the FSA, and had invested more than £1m in projects to reduce it.

We asked Faccenda for its FSA campylobacter results, but it said it had not yet been given them. The supermarkets and restaurant groups told us that they take the subject of campylobacter and hygiene very seriously, and that they would investigate our findings.

As recently as March, the FSA board said campylobacter was its top priority. It was adamant then that consumers had the right to know, as test results came in, which supermarkets and processors had the worst levels of contamination, so that they could vote with their feet and shop elsewhere. The FSA’s director of policy, Steve Wearne, told us that naming and shaming was necessary to make the industry take the issue and the agency seriously.

We asked him why the agency was letting the industry off the hook now.

“Other government departments have reflected to us concerns which are the same as those we’ve heard directly form retailers and producers. We’re not letting the industry off the hook. We’ll publish the results of the retail survey with all the names, when we’ve completed it next summer. If we publish the results piecemeal, other people might draw unwarranted conclusions from partial data and we don’t want consumer being misled or confused.”

The government knows which supermarkets’ poultry is most contaminated, but for now we remain in the dark, despite the fact that two out of every three chickens we buy could still make us ill.

Which? executive director Richard Lloyd said: “The Guardian’s investigation raises serious concerns. Tackling campylobacter has to become a much bigger priority for supermarkets and their suppliers as it is responsible for thousands of cases of food poisoning and the deaths of 100 people every year.

“It’s therefore disappointing that the FSA has gone back on its commitment to publish in full the quarterly data on the levels of campylobacter in supermarket chickens, when it is clearly in the public interest to do so. The FSA must put consumers first and operate more transparently than this.”